Website All About Hardemans

Tarrant County can also lay claim to another highlight this Black

History Month and that is the career and accomplishments of Wesley

Hardeman, the first African-American deputy sheriff in all of

Tarrant County.That might not seem exceptional were it not for the

fact that Sheriff Hardeman, who lived from 1906 to 1966, served as a

peace officer during the difficult Jim Crow years in the American

Southwest. This was 1955, a time when colored people could not drink

from the same water fountains as whites and the law was something

Hispanics and blacks were often found studiously avoiding. But not

Wesley Hardeman. He was early into the right side of law enforcement

when he opened up his own detective agency before becoming a peace

officer. In May, 2007 the 84th state legislature in a proclamation

honoring Deputy Sheriff Hardeman paid tribute to his “strong

religious faith expressed in countless acts of kindness.” Hardeman

was exceptional, it stated, in that “he faced challenges above and

beyond those confronting his white counterparts, including

discriminatory personnel policies and threats to his family, he

discharged his duties with exemplary courage, dignity and

professionalism.”Sheriff Hardeman’s daughter, Bernice McDuffie of Lancaster,

California, remembers that her dad was not supposed to arrest white

people but he did. She recalls one bad moment when her dad and his

partner and her were driving in their police cruiser and two white

officers pulled them over, arrogantly shining flashlights in their

faces. They wrote a ticket to the partner even thought they knew

full well who they were. The man who appointed Mr. Hardeman in 1955,

Sheriff Harlon Wright, was later voted out of office by hostile

electors at the next election even though local TV had proudly

covered Mr. Hardeman’s appointment as deputy.

Deputy Sheriff Hardeman was to win many awards for his skill and

abilities and fair-mindedness, something the community evidently

appreciated as they made him Grand Marshall at many county functions

and invited him to speak in area high schools on good citizenship.

Black History Month should remember Wesley Hardeman – a man who

weathered the storm thorough faith and family.

Hardemans in Dallas

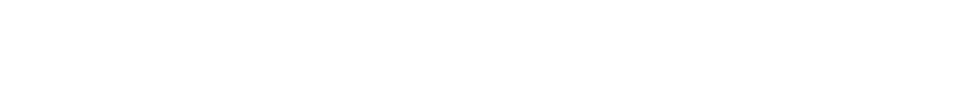

In a Dallas city directory from 1948, there is a listing for Hardeman’s Barbecue. In fact there were two at the time, both of which were located in what was known as Freedman’s Town. It was a segregated African-American neighborhood just north of downtown in what is now Uptown. Those barbecue joints are what built the foundation for a barbecue family that flourishes today – a family whose longevity in Dallas barbecue is eclipsed only by families named Bryan or Dickey.

Chester Field Hardeman’s surviving family isn’t sure which barbecue joint came first, or precisely what year it opened, but the photo above (with the 1948 plates on the Cadillac) and the Dallas Negro City Directory 1947-48 confirm that the Hardeman family was running two joints by 1948. As far as his family knows, this was the genesis of the Hardeman’s Barbecue legacy that endures with three current locations in South Dallas. Chester’s granddaughters, Sarah and Gloria, run their own restaurants on Scyene and Kiest respectively, and Gloria’s son, Jameon, is at the helm in Oak Cliff on Westmoreland. There are no published profiles of Chester Field Hardeman, so his history before the 1930 census is unclear. He was born in Texas in 1901, probably in Travis County. By 1930 he was living and working in Dallas as a landscaper. From a Dallas directory published in 1942 and the unprecedented detail in the 1940 census we know that he rented a house at 1726 N. Central with his wife Annie. By then his occupation was listed as “expresser”, which was probably a delivery truck driver. His family isn’t sure what prompted him to become a restaurateur, but Sarah wasn’t surprised that he jumped into it. “He was always doing something. If it wasn’t barbecue, he’d be selling watermelons, used furniture; he was just a businessman.” He would also have noticed the booming popularity of barbecue in the neighborhood.

In the Negro City Directory 1941-42 for Dallas there are advertisements for Alabama Barbecue’s “Hickory Cooked Meats” and Foster Barbecue who “Slow Cooked with Hickory Wood.” There were 23 barbecue joints in the directory (the cuisine even had its own heading in the slim book) at a time when the black population of Dallas was just over 50,000. Today, the city of Dallas has a population just under 1.258 million and about a hundred barbecue joints within the city limits. Barbecue might be hot today, but nowhere near as popular as it was with the black community in the forties.